Before we delve further into our Elements of Roleplaying Game Design series, we wish to pause and establish a literary foundation upon which we may build. You can find the first post of our new series here.

This essay is about the work—internal work—necessary for one to become a game designer. It’s dedicated it to my friend Sean. It also contains homework.

For the shadow is the guide. The guide inward and out again.

Years before I admitted to myself that I was a game designer, I tried to be a writer—mainly because my mother wanted very much for me to be a writer and/or a teacher. She’s a teacher and a terrific essayist (who doesn’t write because she professes she has nothing to say, but that’s an essay for another day). Perhaps I didn’t try very hard, but I certainly ventured far enough into the terrifying environment of writing fiction to feel the frostbite scorch of its howling winds. To put that in plain terms: From 2000 to 2001 I wrote for and published four issues of a literary zine called New York fucking City, and my mother did not read it.

But this essay isn’t about my mom or my pretentious zine. It’s about Ursula K. Le Guin. In her many essays, Le Guin often waxes poetic about how solitary and lonely are the writer’s many labors. From atop a weathered pillar of experience, she warns that writing is work done alone and within.

All of this, every time, you do alone—absolutely alone. The only questions that matter are the ones you ask yourself.

Reflecting on her bittersweet words in “Talking About Writing,”1 I realize now that I turned away from the path of the writer in my twenties because, standing on the lip of the yawning chasm of that abyss, I was afraid, alone and unprepared. Frigid winds whipped around my feet, urging me to find shelter among the jagged black boulders below but my fear—guttural terror, in fact—shrieked at me to be safe, to retreat. So I reasoned that rather than solitude, I needed the warmth and light of other voices in my work. Thus, feigning resignation and bravery, I turned back from the edge and trudged toward another distant cliff, game design.

When I wrote fiction, I tried to delve into myself and ask the questions that matter as Le Guin instructs us to do but my fear kept me from deeply exploring the region. In the dim light at the edge of my inner writerly terrain, I sought for misshapen stones onto which I etched barely intelligible runes that, once dragged into to the daylit world, not even my mother would read. However, when I designed games—when I wrote bizarre, baroque sets of instructions—my friends not only read them but they created from them countless fictions of their own invention, such that I could never anticipate them all. Thus when I abandoned the lonely path of the writer out of fear, the choice felt right, but arriving at it was required a supreme act of will and even then the path was arduous.

…the journey seems to be not only a psychic one, but a moral one.

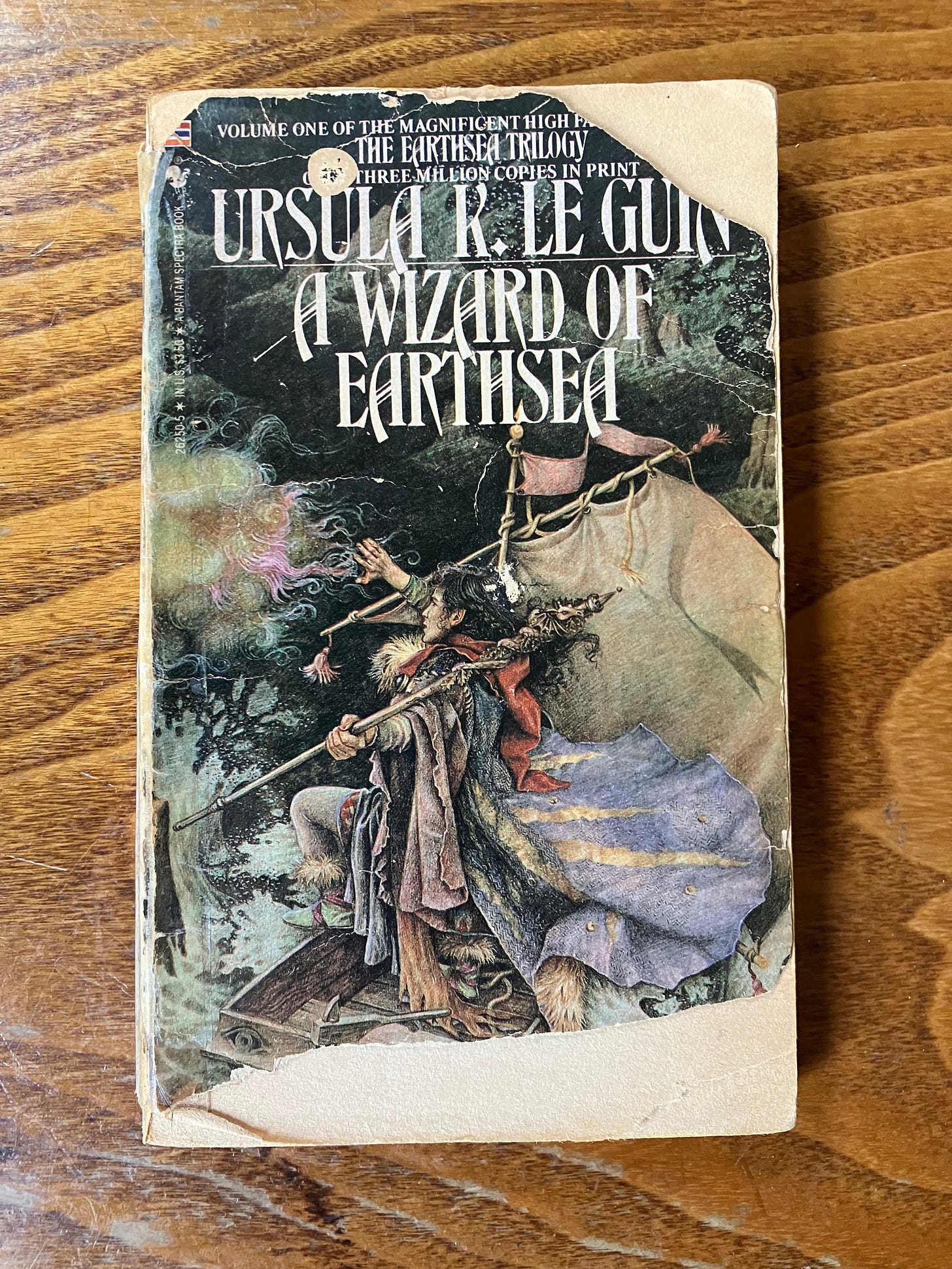

I first encountered Le Guin’s writing in 1984 or 1985, when I was 11 or 12. I know this because I have the 19th printing of the Bantam Books edition of A Wizard of Earthsea. My mother bought it for me. I read it then and I have since reread it a handful of times. Each time I return to Earthsea, I learn more about Ged, wizards, sorcery and myself. Each time I read her words, I am more deeply impressed and humbled by Le Guin’s command of the language of fantasy. Here’s a passage from one of my favorite chapters:

A great hawk came down with loud-beating wings and lighted on his wrist. Like a trained hunting-bird it clung there, but it wore no broken leash, no band or bell. The claws dug hard into Ogion’s wrist; the barred wings trembled; the round, gold eye was dull and wild.

“Are you messenger or message?” Ogion said gently to the hawk.2

Simple, direct and efficient in her execution, yet her ideas are profound.

In 1974, a mere six years after A Wizard of Earthsea was first published, while working on her science fiction novel, The Dispossessed, LeGuin wrote an essay about the roots of and the culture around fantasy literature entitled The Child and the Shadow3. In it, she defends fantasy fiction with her razor-sharp wit. Here she parries conservative criticism of fantasy literature:

Fantasy, to them, is escapism. They see no difference between the Batmen and Supermen of the commercial dope factories and the timeless archetypes of the collective unconscious. They confuse fantasy, which in the psychological sense is a universal and essential faculty of the human mind, with infantilism and pathological regression. They seem to think that shadows are something we can simply do away with, if only we can turn on enough electric lights.4

In the essay, Le Guin also calls upon the Jungian idea that each of us contains a self and a shadow self. The self is clean, functional and flat, but hollow. Whereas the shadow self is difficult to look at while also being far too seductive, and yet still far too bitter a taste to tolerate for any length of time.

Following this line of thinking, she identifies fantasy as the only literature capable of exploring our individual inner, moral, mythological landscapes. In her estimation, it is a medium which guides us on an inward journey to better connect with each other. But to achieve this understanding, we each must admit that we contain both a daylight self and a shadow self. And no glare of light completely eliminates shadow; it merely drives it into deeper corners.

What we need is knowledge; we need self-knowledge.

We need to see ourselves and the shadows we cast.

In her own work, I am often shocked at the suffering, misery and evil she depicts. With dispassion, she summons cruel and inhumane treatments for Ged, Lebannen, Tenar and many others. She insists that this suffering is not superficial titillation, but something that brings us closer to true understanding, to knowledge of the self and to acceptance that evil exists in the world, and each of us is responsible for our role in it.

…as if evil were a problem, something that can be solved, that has an answer…

As every author is, I am frequently asked to describe how my journey began. If you’ve listened to a few podcast interviews with me, you may have heard me talk about how difficult the task was, how I needed to learn skills or how I needed a level of discipline I had never before possessed. But those answers are all of the daylight self, virtuous ideas that one points to: You too can be a writer-game-designer-author-creator if you too have these tools. Yet those answers are half-truths, because tools alone don’t suffice. Tools require blood, bone and sinew to swing and cut.

When I was 27 years old, I was angry, ignorant and lost. In this state, my shadow self alternately threatened to overwhelm me or to abandon me. Either result would have left me half alive, and incapable of being here with you now. Though I flirted with both paths of (self) destruction, I could not bear either. So I would periodically shrink from the edge of the abyss and retreat within myself, clinging to some ragged scrap of life. I hated this time. In my self-loathing, as I thrashed out my internal war between light and shadow, I made many people I loved quite miserable. I was mercurial, irate and wild not unlike the hawk that alighted in Ogion’s hand.

When the weight of this struggle finally cracked the shell of my will—thankfully—fortunately—I chose not destruction, but a creative life: I locked myself in my room and I wrote a game. I went deep into myself. Without knowing anything, I sensed that it was the only path to stay alive.

25 years on from that moment, I realize now that perhaps I did not understand the true nature of my task. For many years I reasoned that I reconstructed my daylight self to strengthen it in order to face outward to the world, but I see now that this is another half-truth. Like Aeneas, like Ged, I needed answers to greater questions found far from the daylit world—those that may be answered only in Hell. Not in the inferno of some cartoonish religion, but in the cold, dark Hell that lives in each one of us.

So down I walked, a torturous track, seemingly lasting many lifetimes. I arrived finally in a forlorn throne room, funereal. On the throne of this Inner Tartarus sat me, my shadow self. My daylight self, bearing his newly acquired tools—a gleaming Sword of Discipline, a Shield of Deadlines and Armor of Schedules—was, in truth, ill-equipped to confront my shade. I could not fight me and win. Oh, I took a few swings, growled, pulled some grim faces, but how could I excise myself and survive? It’s impossible, a paradox. Disheartened, I approached the foot of that ebon throne in supplication and asked the prince of my internal underworld a couple of simple questions:

“What the fuck, dude? Why are you fucking like this?”

My shadow self smiled and replied evenly, “What took you so long? I’ve been waiting for you for your whole life.” Fitting, but not the answer I had hoped for.

In the lives I had lived leading up to that moment, I struggled to express the war within myself. Though I attest to you dear reader that I tried—and failed—to give voice to my inchoate sorrows. In addition to making that zine that no one read, I dropped out of film school, failed to finish ambitious animations, outlined epic comics, abandoned two careers, selfishly broke one heart and then another, and stuffed dog-eared stacks of half-written game designs under my rickety lofted futon.

Facing off against my shadow self in that dismal chamber was an act of desperation. I knew I was lost and that my time to find a true self was running out. Fighting, raging, attacking, those are his tactics, he would have dominated. Instead, I acknowledged the darkness, and spoke to it with a certain respect. And rather than goading me to give up on another fruitless effort, abandon yet another dream or succumb to fear and anger, my shadow self returned the respect.

My gesture disarmed the prince of my darkness and accidentally tapped into our gestalt: I had these newly forged tools; he could supply the requisite sweat, blood and fury. So he took my hand, showed me the way through. Pulling aside the heavy black drapery behind his throne, he lead me into his half of our labyrinth. There, amongst the Weimar shadows, he acknowledged the loneliness and despair that sapped me, and said, “We are not lost so long as we have each other.”

I hated him in that moment. I still do. This story makes him sound so debonair, so smug, but he’s a monster, a minotaur, Asterion, ungovernable and awful. But recognizing that I was incomplete without his pain, fear, lust, hatred and anger was a sobering moment for the daylight self. I’m sure the shadow self felt similarly about his opposite, but speaking to him somehow stills the voices that torment me. And though his nature is wild, capricious and cruel—true to his word—he guided me through the other half of that labyrinth. He knew the way because confusion, doubt and madness are the language of his realm.

And with him as guide, I could at last focus. I could harness the grief and anger present in me—in every human life—and create. Uncomfortable as it was, he made me whole, allowing me to complete my task and bring something new into the world, something found within that contained a kernel of truth, like the stone Lebannen steals from the Dry Land.

Yet even this was not enough. Once we had our detente, I still lacked a voice. The tools were poised, firm in the grip, but they craved a cadence to hammer and cut. I needed some way to express the understanding I had won. So in that desperate moment, dear reader, I reached for the only song I knew, the only one that seemed adequate to the task, the lay that Ursula had been trying to teach me all along: the language of fantasy.

Fantasy is the language of the inner self.

Only language steeped in metaphor and ancient symbols adequately articulates the constant struggle within. To make sense of the constant horrors of the daylight world, I needed the language of fantasy, of signs, of omens—Old Powers, gebbeths, true names, elves, orcs, sorcery, fire, consequences and death. Even the name and sigil of my first game represents a purifying gateway to a realm of death and magic, a spiral carved into a gravestone near Lake Baikal thousands of years ago by someone who understood that the shadow self lay within. It is a warning to the reader: Pass through this portal at peril of your soul.

Once I set forth on this path, my life mercifully clarified. Not that I had peace or success, but the fear and anger receded, like shadows gathered up under a cloak. I had purpose. However, I discovered quite rapidly that the creation of a game is no less lonely and terrifying a path than that of writing fiction. In fact, it may be an even more bitter road. Toiling in solitude to create future surprise and delight for souls whom I will never meet often leaves me questioning my purpose in life. It is frequently miserable, incomprensible work. But it is my work, at least.

All of my dances with darkness and inner turmoil means that my games are accidental products at best, of little commercial value, because they’re the result of my daylight self asking questions of my shadow self. An ongoing conversation of half answers and obscure truths which I require in order to continue to coexist with you—and myself.

On this journey, Le Guin has been my constant companion. Her works are clear-eyed and humane, yet provocative and deep. She speaks in symbols and metaphor. There is a language beneath her words that connects me to her, me to those who are closest to me and me to you, winging overhead on your own hawk’s flight. If I speak your true name, will you alight on my arm and talk with me awhile?

I won’t say that my abiding love of her work has made me or anyone a better or truer human, because I don’t think such a thing is possible (only our inward diplomacy with our own shadows improves us). However, I will venture to say that her work has acted as a map for me—though not of any known land or logic—onto which I chart my position throughout my solitary interior journey. When I look up and see the silhouette of a hawk against the cold sun or bow my head and find tracks in the dry black dust at my feet, I know that I continue on the right path, unaccompanied but never alone, because that shadow is there to guide me.

For we can face our own shadow; we can learn to control it and to be guided by it; so that when we grow into our strength and responsibility as adults in society, we will be less inclined, perhaps, either to give up in despair or to deny what we see, when we must face the evil that is done in the world, and the injustices and grief and suffering that we all must bear, and the final shadow at the end of it.5

Ur-Texts for the Curious Alchemist

Our essays that follow this one examine the fundamentals of roleplaying game design through the lens of the fantasy genre. To get the most out these essays, we recommend familiarity with the following texts:

A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Farthest Shore by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, Tom Moldvay, ed.

Beowulf, translated by J. R. R. Tolkien

Next week we continue our foray into the underpinnings of roleplaying game design with a discussion of what we learned from the Alchemist & the Golem exercise. And we talk about how to create the most simple roleplaying game.

If you enjoyed this essay, you can listen to more of us rambling on far too long about game design on our podcast, The Hypothesis.

Ursula K. Le Guin, from The Language of the Night: Essays on Writing, Science Fiction and Fantasy, “Talking About Writing", Scribner, May 2024.

Ursula K. Le Guin, from A Wizard of Earthsea, The Hawk’s Flight, page 124, Bantam Books, 19th printing, May 1984

Aside from the first, all other pull quotes in this essay are from “The Child and the Shadow.” Substack won’t let me footnote the pull quotes, thus I resort to this blanket attribution.

Ursula K. Le Guin, from The Language of the Night: Essays on Writing, Science Fiction and Fantasy, “The Child and the Shadow", Scribner, May 2024.

Ibid.

As a person that was too afraid to write, who turned back from the shadow, I must admit by not confronting my own inner demons in my 20s led to some tough times in my late 30s. Thanks for sharing Luke.

For years, I saw my need to create as an affliction. Then I realized it was a calling. That comes as a little relief, since a calling can get a person crucified. But at least now I understand the stakes.